I wanted to share this adorable and interesting book. It was written by Edith Nesbitt and is entitled: Wings and the Child. E. Nesbitt was an English author and poet, who wrote or collaborated on more than 60 works of fiction for children, several of which have been adapted for film and television and are still popular today.

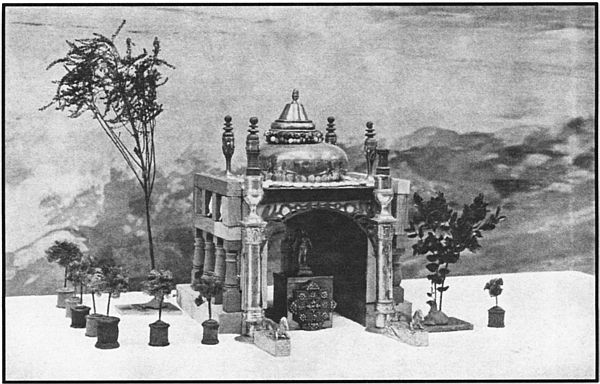

This book, Wings and the Child, is so interesting. It contains cities and little tableaux built from household things. It is also thoughts and considerations on raising children and fostering their imgaination. This was a very new concept at the time, focusing on imagination as an important part of education. This book is well worth a look and you can download it for Free. I will put it in the Library under Children's books Here.

Here is what Nesbitt said of the book herself:

"When this book first came to my mind it came as a history and theory of the building of Magic Cities on tables, with bricks and toys and little things such as a child may find and use. But as I kept the thought by me it grew and changed, as thoughts will do, until at last it took shape as an attempt to contribute something, however small and unworthy, to the science of building a magic city in the soul of a child, a city built of all things pure and fine and beautiful." -- E. Nesbit

And here is an interesting bit from the book that I thought was worth reprinting here. I like how she discusses the ‘new’ availability of mass produced clothes and toys and how they are not in fact boon to imagination. This really struck me as we often discussed this in my 1950s blog as well.

When people's lives were rooted in their houses and their gardens they were also rooted in their other possessions. And these possessions were thoughtfully chosen and carefully tended. You bought furniture to live with, and for your children to live with after you. You became familiar with it—it was adorned with memories, brightened with hopes; it, like your house and your garden, assumed then a warm friendliness of intimate individuality. In those days if you wanted to be smart, you bought a new carpet and curtains: now you "refurnish the drawing-room." If you have to move house, as you often do, it seems cheaper to sell most of your furniture and buy other, than it is to remove it, especially if the moving is caused by a rise of fortune.

I do not attempt to explain it, but there is a certain quality in men who have taken root, who have lived with the same furniture, the same house, the same friends for many years,[35]

[36] which you shall look for in vain in men who have travelled the world over and met hundreds of acquaintances. For you do not know a man by meeting him at an hotel, any more than you know a house by calling at it, or know a garden by walking along its paths. The knowledge of human nature of the man who has taken root may be narrow, but it will be deep. The unrooted man who lives in hotels and changes his familiars with his houses, will have a shallow familiarity with the veneer of acquaintances; he will not have learned to weigh and balance the inner worth of a friend.

FURNITURE TO LIVE WITH.

In the same way I take it that a constant succession of new clothes is irritating and unsettling, especially to women. It fritters away the attention and exacerbates their natural frivolity. In other days when clothes were expensive, women bought few clothes, but those clothes were meant to last, and they did last. A silk dress often outlived the natural life of its first wearer. The knowledge that the question of dress will not be one to be almost weekly settled tends to calm the nerves and consolidate the character. Clothes are very cheap now—therefore women buy many new dresses, and throw the shoddy things away when, as they soon do, they grow shabby.[37] Men are far more sensible. Every man knows the appeal of an old coat. So long as women are insensible to the appeal of an old gown, they need never hope to be considered, in stability of character, the equals of men.

The passion for ornaments—not ornament—is another of the unsettling factors in an unsettling age. The very existence of the "fancy shop" is not only a menace to, but an attack on the quiet dignity in the home. The hundreds of ugly, twisted, bizarre fancy articles which replace the old few serious "ornaments" are all so many tokens of the spirit of unrest which is born of, and in turn bears, our modern civilisation.

It is not, alas! presently possible for us as a nation to return to that calmer, more dignified state when the lives of men were rooted in their individual possessions, possessions adorned with memories of the past and cherished as legacies to the future. But I wish I could persuade women to buy good gowns and grow fond of them, to buy good chairs and tables, and to refrain from the orgy of the fancy shop. So much of life, of thought, of energy, of temper is taken up with the continual change of dress, house, furniture, ornaments, such a constant twittering of nerves goes on about all these[38] things which do not matter. And the children, seeing their mother's gnat-like restlessness, themselves, in turn, seek change, not of ideas or of adjustments, but of possessions. Consider the acres of rubbish specially designed for children and spread out over the counters of countless toy-shops. Trivial, unsatisfying things, the fruit of a perverse and intense commercial ingenuity: things made to sell, and not to use.

When the child's birthday comes, relations send him presents—give him presents, and his nursery is littered with a fresh array of undesirable imbecilities—to make way for which the last harvest of the same empty husks is thrust aside in the bottom of the toy cupboard. And in a couple of days most of the flimsy stuff is broken, and the child is weary to death of it all. If he has any real toys, he will leave the glittering trash for nurse to put away and go back to those real toys.

When I was a child in the nursery we had—there were three of us—a large rocking horse, a large doll's house (with a wooden box as annexe), a Noah's Ark, dinner and tea things, a great chest of oak bricks, and a pestle and mortar. I cannot remember any other toys that pleased us. Dolls came and went, but[39] they were not toys, they were characters, and now and then something of a clockwork nature strayed our way—to be broken up and disemboweled to meet the mechanical needs of the moment. I remember a desperate hour when I found that the walking doll from Paris had clockwork under her crinoline, and could not be comfortably taken to bed. I had a black-and-white china rabbit who was hard enough, in all conscience, but then he never pretended to be anything but a china rabbit, and I bought him with my own penny at Sandhurst Fair. He slept with me for seven or eight years, and when he was lost, with my play-box and the rest of its loved contents, on the journey from France to England, all the dignity of my thirteen years could not uphold me in that tragedy.

It is a mistake to suppose that children are naturally fond of change. They love what they know. In strange places they suffer violently from home-sickness, even when their loved nurse or mother is with them. They want to get back to the house they know, the toys they know, the books they know. And the loves of children for their toys, especially the ones they take to bed with them, should be scrupulously respected. Children nowadays[40] have insanitary, dusty Teddy Bears. I had a "rag doll," but she was stuffed with hair, and was washed once a fortnight, after which nurse put in her features again with a quill pen, and consoled me for any change in her expression by explaining that she was "growing up." My little son had a soap-stone mouse, and has it still.

The fewer toys a child has the more he will value them; and it is important that a child should value his toys if he is to begin to get out of them their full value. If his choice of objects be limited, he will use his imagination and ingenuity in making the objects available serve the purposes of such plays as he has in hand. Also it is well to remember that the supplementing of a child's own toys by other things, lent for a time, has considerable educational value. The child will learn quite easily that the difference between his and yours is not a difference between the attainable and the unattainable, but between the constant possession and the occasional possession. He will also learn to take care of the things which are lent to him, and, if he sees that you respect his possessions, will respect yours all the more in that some of them are, now and then, for a time and in a sense, his.

The generosity of aunts, uncles, and relations generally should be kindly but firmly turned into useful channels. The purchase of "fancy" things should be sternly discouraged.

With the rocking horse, the bricks, the doll's house, the cart or wheel-barrow, the tea and dinner set, the Noah's Ark and the puzzle maps, the nursery will be rudimentarily equipped. The supplementary equipment can be added as it is needed, not by the sporadic outbursts of unclish extravagance, but by well-considered and slow degrees, and by means in which the child participates. For we must never forget that the child loves, both in imagination and in fact, to create. All his dreams, his innocent pretendings and make-believes, will help his nature to unfold, and his hands in their clumsy efforts will help the dreams, which in turn will help the little hands.

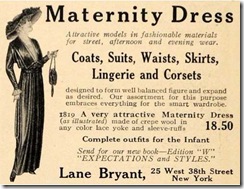

I like how she points out that less is more for children concerning toys and imagination as too, is it for ladies and clothes. Now, speaking of clothes a newer advertised product for women of the early 1900’s was maternity clothes. Though various garments were worn during pregnancy by women, most often women, when showing, went into a ‘lying in’ phase where what she wore mattered little as she was seen by only some family and servants.

Prior to this the new clothing store Lane Bryant wasn’t allowed to advertise maternity clothes. In fact clothes for pregnant women were made to give the woman a more slimming appearance so as not to draw attention to the fact that she was expecting. But after 1904 this had changed and so here in 1913 such advertising is more common.

It’s also of note in this advert that the women are clearly shown actually nursing the child. Not in any shocking way but such an image in an American 1950’s magazine would actually have been considered shocking. Though the general perceived sophistication of those in the 1950’s would have appeared greater than their 1913 counterparts, in fact such a display as a nursing mother would not have been considered ‘appropriate’ in a ladies magazine of the 1950s. We do seem an odd mix, we modern people, of contradictions.

The working classes, as was often the case, hadn’t the money nor time to have the shock and social faux pas to worry about pregnancy. When families often lived in very small proximity or were the children of farmers, the birds and bees and birth were much a daily part of their life. They would have also seen nursing mothers in a much more revealing way than their middle and upper class peers would have imagined. The children of the working classes would have rather opened the eyes of the innocence of the middle and upper classes had they had opportunity to chat; which of course they did not.

A harsh reality that existed for mother and child in 1913 was death. The mortality rates of children were still rather high and mother’s would, more so than today, face often the loss of one child. An interesting connection with breast feeding was the move in the upper classes to artificially feed their children. Up until the Edwardian Age, upper class women often had wet nurses to feed their offspring, thereby still giving them human made nutrition. But, by 1913 it was deemed more fashionable to use the new formulas and to bottle a baby much earlier than their Victorian or earlier counterparts would have even considered. This went on despite such findings such as this:

“A study of breastfeeding patterns in Derbyshire, England between January 1917 and December 1922 illustrates the connection between breastfeeding and infant health outcomes. It was found that most infant deaths occurred in the first few months of life and significantly increased in the first month of artificial feeding. In fact, twenty-two percent of infants died in the first month of life and fifty percent of

all infant deaths occurred in the first three months of life”.

This familiarity with death ran both ways, of course, and the child could often be left mother-less. Death in childbirth was part of many unfortunate children’s lives.

Here we see this illustrated in the 1900 painting by artist Edvard Munch (of the famous ‘the scream’ painting) He lost his mother as a child and this painting depicts that sad even with his little sister trying to block out the reality of their recently passed mother in bed.

As usual I find good and bad in both the past and the present but I can’t help but wonder if in some ways we have our wires crossed today. We have the ability to keep people more healthy and to live longer, yet the costs become far too high for some. This isn’t even a matter of insurance costs but that cost of the actual medications, procedures, and hospital stays. Perhaps insurance coverage should be only part of the discussion but also include costs and how we deal with the act of healing and where it should take place. But, I digress.